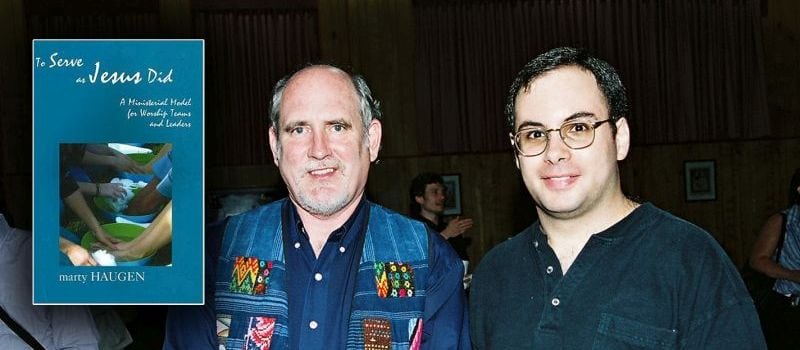

To Serve as Jesus Did: A Ministerial Model for Worship Teams and Leaders by Marty Haugen (Chicago: GIA Publications, 2005). 98 pp.

Most people recognize Marty Haugen’s name when reading it next to the titles in their church hymnals. Many of his songs, including “All Are Welcome,” “Canticle of the Sun,” and “Gather Us In,” resound in many Catholic and Protestant communities throughout the United States each weekend. As a professional liturgical composer who has also had decades of experience as a parish music ministry director, Marty’s impact on liturgy in the United States is already profound. But his book, To Serve As Jesus Did, moves beyond the choir and into the whole of parish life, integrating a rich biblical and pastoral theological vision with insights drawn from concrete experience. Together with his specific suggestions for focusing and improving ministerial practices and commitments, these elements provide a rich well of spirituality that people from diverse Christian traditions can draw from as they seek to enhance their own ministry, and that of their communities.

Haugen’s presentation is both lucid and holistic. While certainly not intended to be an intensely academic work or a comprehensive spirituality of ministry, To Serve As Jesus Did lays out an important foundational understanding of ministry in the twenty-first century, based upon solid biblical and anthropological insights. These form the basis of Marty’s spirituality of ministry. The themes of the relationship between real community, the formation of genuine Christian ministers, and authentic Christian worship are emphasized throughout the book. Each of these threads gets woven together over the book’s eight chapters, and tied together with biblical and Gospel images and stories.

Marty emphasizes the importance of a ministry of presence and the experience of genuine conversion as the bedrock upon which all other ministry is built. Although attention to “presence” has become a cliché in many places, Marty’s emphasis on the importance of a solid life of personal prayer and giving space for attention to the work of God’s Spirit in our lives and the lives of others, is essential. As ministry in today’s church becomes increasingly task-oriented, the recognition that it is quiet time with God that allows us to become good listeners needs to be re-emphasized. A lack of attention to this aspect of ministerial spirituality inevitably leads to frenzied, disjointed, and task-oriented liturgical celebrations shorn of any transformative power. Additionally, conversion is viewed as an ongoing process of personal and social transformation that is neither instantaneous nor easy. It is instead a challenge that dwells at the heart of the Christian community and the Gospel.

This challenge is one that many Christians, particularly those in positions of ministry, often find hard to really put into practice. As Marty notes, while you may find several people at sporting events holding up signs that cite “John 3:16” (“For God so loved the world that he gave his only Son …”) no one is likely to hold up a sign citing “Mark 8:34” (“If any want to become my followers, let them deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me”) (62)! Yet, this is at the center of what it means to be a true minister according to the model of Jesus. This essential message is what the liturgy itself should communicate, but it cannot do so, as long as the hard message of discipleship is not proclaimed or seen in the lives of ministers. It is on this point that Marty’s experience as a liturgical musician is integral. He points out how music can be used in the worshipping assembly to help people claim and live this challenging call to discipleship. Thus, far from downplaying the essential role of leaders in our churches – as some groups focused on church reform emphasize – Marty augments the importance of their role as models of Christian faith, a daunting but necessary challenge to anyone who would take up the ministerial mantle.

Marty also expounds upon the value of the sacred meal of Eucharist that is at the heart of liturgy. Recognizing that contemporary worship is often a place where religious ideologies are fought over, rather than a place where unity in love and common effort is achieved, he presents both a pragmatic and spiritually astute approach that seeks not to destroy or falsely harmonize tensions, but to respond to them creatively and in ways that strive to overcome hostility. His attention to the integration of the Great Tradition of the church, the customs of a particular community, and the creative Spirit-led imagination, serves to bridge theology, spirituality, and pastoral practice in concrete ways. Additionally, his biblically-based reflections on the role of the marginalized invite a thorough re-definition of “success” in ministry and serve as a reminder of the work that remains to be done at the margins of church and society.

One of the highlights of this book is also one of the places that additional information might have been even more useful. I refer to the balanced and concrete suggestions Marty presents at the end of each chapter under the helpful monikers of “headwork,” “heartwork,” and “handiwork”. These suggestions range from the mundane (“Take your watch off during liturgy”) (32) to the eminently practical (“Continually evaluate your worship”) (78) to the sublime (“Widen your circle of the sacred”) (34). While there is nothing earth-shatteringly new in Marty’s suggestions, his presentation of them reminds us of how achievable they are, especially when we might be inclined to think otherwise. However, additional examples drawn from other people’s experiences in ministry might have provided both additional examples and better reinforcement for the suggestions that are offered. While Marty deftly incorporates the insights of key contemporary theologians (e.g. Walter Brueggemann, Richard Gaillardetz) throughout the book, only a few full-time ministers are cited by name, besides Marty himself.

Additionally, there are places in the text where more explanation or greater detail would be of great benefit. For example, Marty’s presentation of a conversion as process rather than instantaneous experience (38) could benefit from including a practical approach by which ministers, whose understandings of conversion differ, might work with one another in spite of this difference. Also, in mentioning the various ways in which parishes attempt to structure liturgical celebrations which incorporate both elements of tradition and contemporary and multicultural customs (71), a more attentive practical analysis of what works and what doesn’t seems to be an area of analysis that begs for greater insight today. Finally, how can a member of the community, who may not be as conversant with the liturgical tradition and contemporary theology as Marty would like them to be, be in a position to provide the meaningful analysis of concrete liturgical experiences for the ministry team that he hopes they can offer (77)? In the end, these are all minor points, but, if addressed, they could offer even more food for thought in a future expanded edition.

In sum, then, To Serve as Jesus Did, is an easy and informative read that can serve as an entry point into the ongoing dialogue about the nature of ministry in today’s rapidly changing church. It has the added value of being ecumenical in nature, and I would heartily recommend it to any minister or ministry team for common reading and discussion, as well as to ministerial formation directors and programs preparing students for active ministry.

Request Dr. DelMonico's professional services for a liturgical, ministerial or leadership consultation, or for an academic or public presentation.

Request Dr. DelMonico's professional services for a liturgical, ministerial or leadership consultation, or for an academic or public presentation.